It’s more than a year since I first picked this book. I’ve let them go a few times. Man, this was a long one! But it was worth. I picked this book early 2022 because I wanted to learn about data. I’ve always been curious about data engineering, and challenges that come by in that space of work. I remember interviewing for Data Eng position at Shopee right after graduating undergrad, and totally blanked out terribly when asked questions like what OLAP is 🫣. This book was my redemption.

It helps navigate through the diverse landscape of data storage/processing tools and systems, and understand its limitations. Hopefully then, we could decide which are appropriate given the challenge of quantity, complexity, and velocity of data of this information age.

Note: This post is my attempt of summarizing. None of these thoughts belong to me.

There was too much nuances to think of. I can’t help but bring these ideas to ongoing discussions in my work (e.g. bringing fraud data like shop close events across the company, but want to keep actions and policies synchronous. Dataflows is bi-directional). I’m hopeful that I’ll come to this for reference many times in the future.

Table of Contents

- Part I: data stored in 1 machine

- Part II: distributed across machines

- Part III: Guarantees

- Part IV: derived data in heterogenous system

- Part IV: Future of data systems

- Miscellaneous

Part I: data stored in 1 machine

In the ‘ideal system’, what we want is Reliability, Scalability, Maintainability. Reliable systems tolerate faults of the inevitably unreliable parts. The system should tolerating hardware faults (ie. redundancy or software techniques), systematic error (ie. evaluate assumptions and edge cases, testing, isolation on failure, monitoring), human error (ie. sandbox environments, easy recovery, telemetry). Sometimes we choose to sacrifice it to reduce dev/operational cost, but be conscious when we cut corners. Scalable system manages the side-effects of growth in data/traffic/complexity. Load is described by ‘load parameters’ (ie. rate of request, distribution of followers, r/w ratio, simultaneous user, hit rate, common operations..), then design the architecture around that load param. (e.g. make expensive fan-out write and fast read if R>W rate). What happen when load param increases? How much can you tolerate? (affects on throughput, distribution of response time, etc). Worry about peak, not just average. (ie. P90 edge cases can be expensive) Maintainable system cares about operability (e.g. monitoring, dependency updates, anticipate issues, documentation, security, etc), simplicity (e.g. well-defined abstractions), evolvability (agile across large data systems). Maintenance cost > cost of initial development.

Different data models / query languages

Models reflect how we think of problem. Systems are built off layers of data models (ie. domain object, storage structure, memory/network, hardware, etc). Relational DB vs NoSQL (many non-relational db models) In relational db, a general purpose ‘query optimizers’ abstracts away access path of execution. In document db, there’s schema flexibility (implicit schema-on-read. So app need to explicitly handle any structure changes and require no data migration, saving downtime), performance from data locality (however, since entire doc is replaced on updates, keep them small, and avoid increasing its size to avoid reallocation). It’s good for contained data, supports 1-many (nested tree), but is expensive for many-1/many-many references, joins, or may need to denormalize. Relational & document db is converging over time (e.g. json column in SQL db, relational-like join support in Rethinkdb, etc.) Graph-like models Are more natural for complex interconnected data (e.g. social, web, road network). Can run algorithms like shortest-path and page rank. Graph can be heterogenous, a datastore containing different types (vertex representing people, location, event, checkin, comments). You can think of it as being stored in Vertices table (id, properties) and Edges table (id, tailvertex, headvertex, properties). Allow flexible and evolving schema, and dynamic number of joins. Querying recursively walks through the variable-length edges on the graph to look for a match (recursive CTE in SQL is much more complex)

Query languages: Declarative (specify pattern, hides/decouple implementation, less expressive) vs Imperative (define steps to achieve goal, hard to parallelize/optimize). Map-reduce is in between imperative/declarative and pretty low-level (SQL can be implemented as series of map-reduce), but its restricted to a pure function (no side-effects so it can run independently).

Indexes

Knowing how storage engines work helps you select & tune a storage engine to perform well on your load. Let’s talk about indexes… Index is an additional metadata to search data in < O(n) time. Fast read but slow writes from overhead (⚠️ tradeoff based on your query patterns). Secondary index helps perform joins or a field-search (ie. find all {table} with {indexed column condition}), isn’t unique. A B-tree or log structured index can be used.

2 approaches of indexing / storage engines:

- Log-structured indexes: Many db use immutable append-only data file (log). Pros: sequential write is much faster than random writes, simpler concurrency and crash recovery. A simple example is hash indexes: an in-memory hash map

{PK: byte_offset_in_disk}. You could have a background job to perform ‘compaction’ (normalizing keys), ‘merge’ segmented files, store it in new segment. During that time, new write request goes to new segment, new read requests goes to old segment. Good for high write frequency, but must fit in memory (random access and growth makes hash map on disk hard) and isn’t good for range queries. A better example is SSTable (sorted string table) / LSM trees: like hash index, but sort the segment files by key. It makes out-of-memory compaction easy with merge-sort, allow sparse index and range queries. Keeping it sorted in disk is possible (b-trees), but even easier in memory (i.e. red-black trees, avl trees). In-memory trees are called ‘memtable’, and you write it to disk as new SSTable segment. SSTable then gets compacted & merged on scheduled background job. Problem 1: recent writes to memtable is lost on db crash. Solution is to keep separate log on disk to append writes and can be cleared once memtable is written to disk. Problem 2: look-up on non-existent key is slow, as it looks through all segments. Solution is ‘bloom filters’. - Page-oriented indexes (ie. B-trees) is more widely used. B-trees are also sorted by key, but structured as a tree of fix-size mutable pages instead of variable-sized segments. Each page has sparse keys and in-between keys is a reference to another page that defines keys within that range. Adding new key adds to the right page, or if full splits the page in 2 halves. Tree remains balanced. (fun-fact: 4-level tree of 4kb pages with branching factor of 500 = 250 TB). Problem 1: a crash in between page mutations can lead to corrupted index. Solution is a separate ‘write-ahead log’ (WAL) to write operation before executing them. Could also use ‘copy-on-write’ scheme, so it’s not mutating directly. Problem 2: Tree mutations 🌳 must be protected with latches/locks for concurrent writes. Problem 3: Is hard to maintain locality of leaf pages to be positioned sequentially in disk to optimize range queries disk seeks. Unlike LSM trees which writes merged segments in one go.

Typically LSM-trees has faster writes, whereas B-trees has faster reads, but benchmarks depends on your workloads. LSM-trees have high write throughput with sequential writes, compress better with no fragmentation; but its background compaction job can block IO, thus p90 response time of lsm-tree is less predictable. It also requires compaction write bandwidth to keep up with incoming write throughput (otherwise you run out of disk. Need to monitor ingress or throttle)

Clustered index stores entire row as index’s value (e.g. InnoDB PK) vs Non-Clustered index where value is a ref to heap. This allows for multi index, but needs to reallocate pointer if row size increase.

Multi-column indexes can be used to query multiple cols together without an O(nlog(n)) search (e.g. long/lat, rgb, time/temp). Concatenated index is most commonly used: combine fields into one key, i.e. ‘firstname lastname’, order matters depending on field of search. B-tree/LSM wont work on multi-dimensional range (i.e. querying locations within a long/lat range), so either need to convert to 1D (e.g. using space-filling curve) or use specialized spatial indexes like R-trees.

Fuzzy indexes can search for similar text or mispelling. Lucene uses SStable to store a term dictionary {term: [...doc_ids]}. Its in-memory index is a FSA of characters, which can be transformed to ‘Levenshtein automaton’ to allow search for words within some edit distance.

Data Models

In-memory databases: instead of storing data in disks, we can get durability by distributed systems and logs (ie. VoltDB, MemSQL, RAMCloud, Redis, Couchbase). Using in-memory is faster, avoid overhead of encoding the structures on disk-write, and allow data structures like priority queue/sets (in Redis).

OLTP (online transaction processing) DB stores state with low-latency R/W. The bottleneck is often disk seek time so need indexing. OLAP (online analytic processing) is used to read large records to aggregate, write bulk or store event stream. The bottleneck is often disk bandwidth to scan huge records so needs encoding/compression (e.g. Apache Hive, Spark SQL, Apache Drill)

Data warehouse runs expensive ad hoc analytical queries without affecting OLTP operations. Read-only copy of all OLTP data. Uses ETL to be extracted, transformed to analysis-friendly schema, cleaned up, and loaded to warehouse.

Star schema (aka. dimensional modeling): A Fact table represents timestamped event, with columns either attributes or a FK to a Dimension table (the 5W1H of the event, such as date/product/customer).

Column-oriented storage: Stores each columns together instead of the rows. Support OLAP access pattern that typically queries for few columns but large records. Also applies to non-relational data (ie. Parquet). Allow data compression before storage since most column values are repetitive (ie. one-hot-encoded bitmap for each distinct value in the column also allow efficient searches using bitwise operation; vectorized processing; and saves bandwidth since more data can be loaded in memory/cache on operation).

Sort order: every col can be sorted in ways that benefit the queries (ie. sort on date). You can have multiple sort keys, or even redundant data sorted in different ways. They make writes more difficult, but not a problem since data warehouse is read-only.

Materialized views: a matrix of cached aggregations (ie. SUM, COUNT..) where each FK of the fact table is a dimension (ie. data cube / OLAP cube)

Data formats, evolving schemas, serialization

When data format / schema evolve, different version of code and data can coexist. You either need backward compatibility (new code handles old data) or forward compatibility (old code handles new data, often by ignoring additions)

For Thrift/Protobuf: Adding required/optional field is ‘forward compatible’. Adding optional field is ‘backward compatible’. Removing optional field is ‘backward compatible’. Removing required field invalid. For Avro: You can only add/remove field with default, since you break compatibility when reader can’t find a default on a schema mismatch.

Encoding/serialization: in-memory objects (optimized for access) is translated to byte-sequences when you write/send data.

Language specific encodings (java’s serializable, python’s pickle, ruby’s marshall) is convenient but language specific, vulnerable to decoding arbitrary byte sequence, unable to version, and bad performance. So prefer standard encodings (i.e. json, xml, binary variants).

Limitations: XML/CSV can’t distinguish number/string. JSON can’t distinguish integers/floating-point, so large numbers are better off a string, since languages with floating-point IEEE754 like JS can’t parse it accurately. JSON/XML don’t support binary strings, so need to interpret as base64 hackily. Difficult to enforce schemas.

When internal data has no pressure for interoperability, consider Binary encoding. It’s more compact, schema is always an up-to-date documentation, track backward/forward compatibility, allow type checking for typed languages. (1) Thrift & Protobuf are 2 binary encoding libraries. Both has schema so no need to include field names, but a field tag/identifier (inc #) for schema evolution. Schema is in an IDL format and code can be generated to encode/decode that schema in language of choice. (2) Avro is another binary schema. Super compact because encodings only has values without its field-name/tag/datatype. Encoder/decoder schema must be compatible, but don’t have to be the same. Comparing both the writer and reader schema, Avro decoder provides a schema resolution (ie. matches fields by name. If in writer but not in reader schema, it’s ignored; forward compatible. If expected in reader but not in writer schema, it fallback to reader’s default; backward compatible). The reader can fetch the writer’s schema either via the beginning of a large file, via the writer version number associated with the record in db, or via the beginning of network connection (ie. Avro RPC). It’s friendlier for dynamically generated schemas, since you don’t need to manually assign field tags like in Thrift. It also makes code generation optional so you can look at data directly as long as you have the schema.

The concept of compatibility applies the same for other ways of sending data: (1) via DB: is backward compatible for its ability to decode what’s written in the past. Forward compatible matters for example on rolling upgrades when new code inserting data doesn’t break old code reading it, and when old code tries to modify data from newer schema it should keep the new schema intact (must be taken care in the app code). (2) via Service Call: data encoded/versioned between clients and server API should be compatible. RPC frameworks use binary encoding for performance (ie. gRPC uses protobuf) with inter-organization requests as its focus. Whereas REST is dominant for public APIs for its vast ecosystem and simplicity without code generation. Server is typically updated before clients, so you only need backward compatibility on request & forward compatibility on response data. When service can’t force clients to upgrade during compatibility-breaking change, they need to support multiple versions. (3) via Message Passing: Message is a byte sequence so can use any encoding. A use case is in Actor programming model (i.e. Elixir supervisor. Each actor communicate via messages, and can scale over multiple nodes since addresses can be local/remote and assumes messages may be lost). On rolling upgrades, you’d need to worry about compatibility between messages sent.

Part II: distributed across machines

You can distribute data for scalability, fault tolerance / availability, geographical latency. But comes with complexity, constraints, tradeoffs. There’s 2 common way to distribute data: Replication vs Partitioning/Sharding.

Replication

Single-leader replication: Leader-based replication: client writes to leader, leader sends to its followers the change-stream / replication logs, each followers apply changes in order. Read from any node, but write must go through the leader.

Sync vs Async replication: On Sync replication, leader waits till data is propagated to all followers before confirming the write. On Async Replication, leader doesn’t wait. On Semi-sync, one of the follower is sync to ensure latest data in at least 2 replica. Sync gives better guarantee/durability but blocks write.

On new follower setup: take a snapshot of the leader, copy to the follower, follower requests the leader’s replication log for changes since the last snapshot, catch up. On follower failure, follower compares and catch up with the leader’s change-log. On failover (leader failure), new leader is elected, the client and other followers including old leader are reconfigured to ack the new leader. Failover challenges include discarding async writes when old leader hasn’t replicated it (cause inconsistency), deciding timeout before leader declared dead (unnecessary timeouts on transient load spike vs long recovery time when it fails), split brain situation, etc. Thus failover is often performed manually.

Different ways to implement replication logs: (a) Statement based replication: forwards the instructions. But operation must be deterministic and ordered. (b) Write Ahead Log (WAL): the low/byte-level write logs are forwarded. But needs downtime on db upgrade. © Logical Log replication: a separate log from the storage engine log, with per-row granularity. Nodes can run different DB versions. Logical logs can be easily parsed for CDC. (d) Trigger-based replication: move it up to the app layer / triggers / stored procedures, to run custom code. E.g. if you want to replicate subset of data or perform conflict resolution.

Replication guarantees:

- Eventual consistency: On async replication, a read-replica could be stale. But will be eventually consistent. ‘eventually’ (replication lag) is vague.

- “Reading your own writes” / “read-after-write” consistency: guarantee you read changes you write instantly. Implementations: (1) Read modified data from the leader, (2) Client/server can track time since last update and only use follower with replication lag within 1 min. For consistency across device, you may need to route a user’s devices to same replica and somehow maintain a central timestamp.

- “Monotonic reads” guarantee you don’t go to older replica along a read sequence. So user don’t see things move back in time, like making several reads and seeing the comment appear & disappear. Implementation: restrict user to read from 1 replica.

- “Consistent Prefix Reads” guarantee if sequence of writes happen in some order, anyone reading will see them in same order. So observer don’t see answers appear before the question when reading from multiple replicas/partitions. Implementation: restrict that any causal related event writes to the same partition, or use algorithm to track causal dependencies (see footnotes)

- See more later (ie. Consistency guarantees)

Dealing w these issues in app code is complex. ‘Transactions’ try to hide these guarantees. Stronger guarantees are expensive, so use it sparingly.

Multi-leader replication:

Use multi-leader replication to scale writes, add performance, and tolerate outages. But needs write-conflict resolution for concurrent writes. A common strategy is 1 leader per datacenter. Each leader acts as followers to other leaders. Is complex and should be avoided when possible.

Other use cases: (1) Offline db has same architecture as multi-leader replication. Each device is its own write leader that asynchronously synchronize over unreliable network. Tools like CouchDB make multi-leader configuration easier. (2) Real-time collaborative editing apps.

Detect/resolve write conflicts: (1) Avoid them when possible. I.e. route user through only 1 datacenter. (2) Resolve order/inconsistent state on write via timestamp/uuid (i.e. last write wins) (It’s prone to data loss on concurrent writes but is acceptable for uses like caching) (3) Merge/concatenate values if possible (4) Resolved on read by storing the conflicted data and resolving it with a user-prompt. (5) Use algorithm to detect whether its a ‘concurrent issue’ or ‘happens-before’ (see footnotes). Version vector could be passed along the replicas. Each client override/merge data for ‘happens-before’ causality and keep all ‘concurrent’ writes (for resolution).

Replication topologies: describe how write is propagated through the leaders (ie. circular, start, all-to-all). Tradeoff: single point of failure vs causality issues (some links are faster than others leading to disordered messages on arrival. Similar problem to ‘consistent prefix read’. To order events, use ‘version vectors’, but many systems implement conflict detection poorly so read/test your guarantees carefully)

Leaderless replication (aka dynamo-style db):

Client (or a coordinator node) sends writes to many replicas. Writing only need majority of acks. Reading are also sent to several nodes (version # is used to determine which value is newer). Pros: high availability (no failover), low latency, tolerate stale reads. Cons: not fault tolerant against network failure.

General quorum rules: With n replicas, write must be confirmed by w nodes and reads must query at least r nodes. We’ll get up-to-date value as long as w+r>n. Balance w/r values based on # of node failures you can tolerate, but don’t take them as guarantees as there are edge cases (ie. concurrent writes, rollback hasn’t occur after failed write, etc).

Copying over missing data to stale replicas can be done via (a) read-repair (reader fix any stale it found), or (b) anti-entropy run background process to copy over missing diffs

Monitoring staleness is important for db health. On leader-based replication, you could track replication lag metrics (leader’s replication log position - follower’s position). In leaderless replication, there’s no fixed write order so this is difficult.

Sloppy quorums (optional. To tolerate network failure): When quorum isn’t reached (ie. potential network failure), accept the writes anyway rather than returning errors. Write it to your neighbouring nodes temporarily, for durability and not part of the quorum. When nodes recover, return the write to the home nodes - ‘hinted handoff’.

Partitioning/Sharding

For larger dataset / high query throughput, you want to scale across many disks and query partitions independently. Usually combined with replication for fault tolerance. Beyond simple R/W, parallelizing query execution (multiple join, filtering, grouping, aggregations for analytics) amongst partition/nodes is a hot specialized topic.

Goal: Make partitioning fair (equal data and equal query throughput). Else, it’s ‘skewed’. A partition with a high load is called ‘hot spot’.

Ways to partition:

- By key range: like a dictionary, you directly know where to go. Depending on tne data distribution, partition boundaries would need to adapt (e.g. when A-B > T-Z). Cons: r/w access patterns can lead to hotspots, so design keys carefully.

- By hash of key: hash_function(key) => partition. Data is uniformly random distributed, but doing range queries becomes tricky since no sorted order. Skewed workload can still exist (ie. a celebrity tweet). A technique is to split the hotspot keys into many and concat it with a random number, but this needs additional bookkeeping.

- Hybrid approach: compound key. The first part identifies the partition and second part for sorts it.

Partitioning secondary key (SK index) is more complex: 2 main approaches:

- Document-based partitioning / local index: The row’s SK are stored in the same partition as the PK. Writing a document updates only one partition, but expensive read since SK of all documents must be gathered from all partitions.

- Term-based partitioning / global index: Partitions are determined by the term/SK itself, similar but independent to how PK is partitioned. Once you find the SK record, which contains array of refs to PKs, you could follow those docs across multiple partitions. Easy read, but expensive write since multiple SK indices of the document is spread across partitions (often async, which breaks read-after-write consistency).

Rebalancing partitions: You need to move data around partitions when adding cpu, memory, failover, etc. How do you maintain fair distribution, stay available, move sparingly to minimize time and load? Strategies: (1) Fixed number of partitions: Create more partitions than nodes so node:partition is 1:many. Partitions are stolen/moved between nodes. Operationally simpler but it’s hard to configure the right # of partitions ahead of time; high overhead when partition size is small, but hard to rebalance if it grows too big. Ideally, partition size proportional to data size. (2) Dynamic partitioning: Allow partition to split/merge. Number of partition proportional to data size (3) Fix number of partitions per node: When number of nodes change, partitions splits/merge its data across.

Rebalancing is dangerous, keep human in the loop to prevent operational surprises. It’s an expensive operation with large amount of transferring.

Service discovery (how does client find the partition, i.e. routing tier). Keeping routing tier up-to-date is challenging because of consensus - use coordination service like ZooKeeper to track this mapping, or have each node implement gossip protocol, etc.

Writing often involve multiple partition. What if one fails? -> transaction!

Part III: Guarantees

Transactions

Transaction are created to ignore many error scenarios and concurrency issues which are hard to debug and test. Multi-object transaction is needed for things like maintaining FK, updating denormalized data, updating secondary indexes.

Guarantees transaction provides: ACID - Atomic: abort/rollback if transaction cannot be completed/committed. Prevent intermittent state so it can be safely retried. E.g. For single-object operation we can use crash logs, atomic operations like compare-and-set. - Consistency (shouldn’t belong in acid): when transaction preserve validity about the data (invariants) that must always be true. However, this consistency is a property of the app code and not the DB. - Isolation: concurrently executing transactions are isolated from each other. Serializability means transaction can pretend it’s the only transaction running, and if there’s another transaction they’re committed serially. There are weaker form of isolation levels to tradeoff for performance. E.g. lock each object - Durability: promise that once committed, data will persist despite faults/crashes. In practice, there’s no guarantee - lots of bugs happen at low-level.

Isolation levels

Serializable isolation comes with performance cost and many DB use weaker isolation levels to protect against ‘some’ concurrency issues. Most implementation don’t satisfy formal definitions of these guarantees, so don’t blindly rely on tools; understand the problems that exist & how to prevent them.

a) Read Committed guarantees 2 things: (1) No dirty reads: other client can’t read between transaction before it’s committed. Only read committed data. Implementation: Read-locks blocks reads during long-running transaction. Instead, DB can store old committed value and serve them for reads during the transaction (2) No dirty writes: other client can’t write to the resource in between transaction. Only write to committed data. Implementation: row-level write locks

Skew reads problem (non-repeatable reads) when there’s a write transaction between 2 reads you might see inconsistency between the 2 reads. Although you could do a refresh, this is less tolerable for backups/long-queries that observe the db at different points in time.

b) Snapshot isolation / Repeatable read: transaction reads from consistent snapshot. Implementation: DB maintain different committed version of object for each transaction (aka MVCC ‘multi-version concurrency control’). In MVCC, each transaction gets incrementing id, and updating an obj will mark-delete + create-new-block with its id. All transaction only consider blocks from committed transactions that it sees at its start. For indexes, you could keep versions with copy-on-write B-tree, or use one index for many versions and later filter visibility rules via txId.

Lost-update problem: when 2 write transactions (in form of read-modify-write) are concurrent, you risk losing earlier write (ie. 2 concurrent increments, updating documents/page, ..).

Solutions: (1) Atomic write operations: if possible avoid read-modify-write cycle with atomic operations (ie. use UPDATE .. SET value = value + 1 WHERE ...). Not possible for cases like text editing. (2) Explicit locking: lock resources updated by the transaction with app code. (ie. FOR UPDATE) (3) Auto detect lost updates: let concurrent transactions run in parallel and redo if race did happen. Detect race using same algo as snapshot isolation. Nice if db use this since it’s automatic, not mysql. (4) Compare-and-set: Only set when current val match previous read, else retry. Check for db support

On replicated db, lost-update can happen on 2 concurrent writes happening on different nodes. Locks don’t work because there’s no guarantee of 1 up-to-date data. You need to detect concurrent write and let app code resolve the versions (see notes on resolving conflict).

Write-skew problem: when 2 transaction read same set of objects then update them. Generalization of lost-update problem, but harder since there’s now multiple objects involved, you can’t use db constraints on multiple objects. (Ex1. 2 doctors concurrently try to leave on-call at the same time, both can succeed with its own snapshot isolation even when they shouldn’t. Ex2. booking conflict for a meeting room).

Solution: You could use db triggers, serializable isolation, explicit locking (doesn’t work for Ex2 since it checks for absence and no object to attach lock to. You could create rows to represent empty slots/resources that can be locked - approach is called ‘materializing conflicts’, turning phantom into lock conflict). Phantom: where a write changes search query of another transaction.

c) Serializable isolation. Implementations:

- Execute in serial order: A single threaded loop execute transactions. It’s made possible with development of bigger RAM, transactions are normally short-running. Throughput is limited but avoid concurrency issues. Single-threaded usually disable multi-statement transaction since that’ll kill throughput with lots of network delay; instead puts transaction code in stored procedure so everything gets executed from db. You can potentially scale throughput of single thread by using multiple cores and partition data.

- Two-phase locking 2PL: Require Shared-lock for reads, and Exclusive-lock for writes. Exclusive-lock blocks everything and Shared-lock blocks exclusive lock. There’s also Predicate-locks/Index-range-locks which locks group of rows matching some condition. Transactions only release all of its locks at the end, so it’s possible for deadlock, in which the DB would abort one of them. Perform significantly worse than weak isolation, reduced concurrency and queuing, due to acquiring/releasing locks.

- Optimistic concurrency control like Serializable Snapshot Isolation SSI: On top of snapshot isolation, SSI use algorithm to detect serialization conflict, and should abort in situations where transaction acts on outdated premise (someone has changed something it thought was true). A read premise is outdated if (a) the MVCC read snapshot is stale due to a write from uncommitted transaction before it. At the point of premise, uncommitted transaction was ignored because it doesn’t know if they’re going to write. (b) a write happens after the read: Like 2PL’s locking, we could do the same but only as a trip-wire to notify that row may be outdated. Checks if it’s indeed modified at the end of transaction.

- SSI provides full serializability with small performance penalty, since no locks. Best for short transactions and on low contention since it’s less likely to run into aborts. It’s optimistic as it assumes everything’s good, and checks for violation before commit (abort and retry).

Providing guarantees for distributed machines. 😓

For single-node computer, total failure is better than partial failure. Makes it deterministic. However multi-nodes introduces network latency, availability, high failure rate, geographical distance, etc. We’re forced to build reliable system from unreliable components, by building high-level concepts on top of it.

Networks

Often the only way to communicate is across machines. With asynchronous packet networks you can’t guarantee it arriving. Was it processed before the response were lost? Was there delay? Was it delivered?

Defining, testing, and detecting network faults is important, otherwise arbitrary things like data-loss. See how your system reacts to the chaos monkey (ie. node failure). You can declare node is dead if timeout keeps elapsing on multiple retries.

Timeout tradeoff: Long timeout (long wait) vs short timeout (cascading failures, redundancy). You could monitor and set timeout based on expected delays adaptively with a Phi Accrual failure detector.

Delays happen due to network congestion and queuing. As incoming data increases, the switch queue will fill and packet starts dropping. There’s also OS queue if CPU is busy, queue on sender for rate limiting, queuing on VM if it gets paused, etc.

Use UDP for latency-intensive apps like calls. Has low reliability (ie. don’t retry) but avoid network delays.

Why can’t we make network synchronous? Circuit-switch (ie. fix-line telephone network) is extremely reliable but assume a fixed amount of call bandwidth. Packet-switch protocol is used for TCP connection because they’re optimized for bursty traffic with no particular bandwidth requirement. Tradeoff: You get variable delay in dynamic allocation, but wire is maximally utilized and cost less. You get latency guarantees in static allocation, but reduced utilization make it expensive.

Clocks and timing issues

Each machine has its own inaccurate quartz clock. To sync time, NTP is commonly used - where clock is adjusted to a server group, which is adjusted by more accurate sources like GPS.

We depend on clocks: timeouts, timestamps, expiry, scheduled jobs, time metrics, generating consistent txID for snapshot isolation

The 2 kinds of clocks are (1) Wall clock time which usually sync-ed with NTP but could move back in time so is unreliable for measuring elapsed time. (2) Monotonic clock which is guaranteed to move forward in time. Used to measure duration/elapsed time. NTP can speed/slow it down but can’t move it back in time.

There’s still plenty of ways for clock sync to go wrong (i.e. NTP is limited by network delay too, process could pause at any time). And often this fails silently (data loss). If you care, you need to monitor clock offsets between machines and build robustness around it. Issues are amplified in distributed system because there’s no shared memory you can rely on. A leader could arbitrarily pause and continue without noticing it slept. 😴

You could prevent processes from pausing if you try hard enough: In embedded/critical systems, real-time means it needs to meet timing guarantees (nothing to do with performance). It needs expensive support from the whole stack (e.g. real time operating system RTOS guarantees cpu time, library functions document worst-case time, limit GC)

Don’t rely on clocks to order events. (i.e. LWW last write wins strategy won’t work. The definition of ‘recent’ depends on incorrect clock). A safer alternative is logical clock.

Nodes just can’t work together

Truth is defined by majority: there’s only one majority and it decides the fate of the system. Even if a node believes it’s the ‘chosen one’, it doesn’t mean the majority agrees, and acting as if it’s the chosen one could corrupt the system. To avoid the misleaded node from disrupting the system, you could use technique called Fencing: an incrementing counter called fencing token is given every time a ‘chosen one’ is granted. The resource would collect these tokens, and reject writes if it had processed one with a higher token. E.g. for zookeper lock service you could use zxid/cversion as the token since they’re monotonically increasing.

Byzantine fault: when nodes deliberately lie (e.g. faking a fencing token) it’s harder because now they’re unreliable and untrustable. The consensus problem in these environments are called ‘Byzantine Generals Problem’. E.g. in aerospace env, data in memory/cpu register could be corrupted by radiation and node can act arbitrarily, fraud prevention in P2P networks. Solution protocols are complicated and often impractical. Byzantine problem isnt a problem in web apps where server/firewall authorizes request and prevents malicious clients.

A bit about designing guarantees

Although it seems like distributed systems can’t guarantee anything, you can design system models with certain assumptions of its behavior, design the world to satisfy those assumptions, then make guarantees.

Common system models for timing assumptions: (A) Synchronous model: bounded clock/network/process-pause delays. Often not practical (B) Partially synchronous model: sometimes exceed bounds but behave well most times. © Async model: don’t rely on timing/clocks/timeouts.

Common system models for node failures: (A) Crash-stop faults: node either works or crash (B) Crash-recovery faults: node can recover after crash. You can preserve state in disk. © Byzantine faults: nodes can do anything including decieving others

Distributed algorithms are then designed based on these models. 2 categories of properties for an algorithm’s correctness: (A) ‘liveness property’: something eventually happens. Can’t point to specific time (i.e. availability) (B) ‘safety property’: nothing happens, and if it did we can point to specific time (i.e. uniqueness, monotonicity)

Unfortunately, real world don’t always follow system model assumptions. Yikes.. Theoretical analysis is still important, but so is empirical testing,

Consistency (at the cost of fault-tolerance & performance)

Consistency guarantees (of replicas) - Eventual consistency (see replication) is the weakest. Bugs are hard to find by testing. - Linearizability is the strongest. Create illusion of a single replica and no replication lags between nodes, by add another constraint that if a client reads value r, all subsequent reads should also be r. - Examples where we need linearizability: (a) In systems that elect leader by granting locks - everyone need to read and agree of the most recently elected leader. (b) To provide uniqueness guarantees like picking usernames. © In other constraints like preventing bank balance from going negative, booking same seat on a flight, sell more than available stock. (d) In cross-channel systems, delay between data passing through multiple channels can disrupt system dependent on reading both channels consistently. - Implementation of linearizability: (1) If you r/w from single-leader replication && doesn’t use snapshot isolation && don’t read from a stale leader during failover. (2) Use consensus algorithm (i.e. zookeeper / etcd). - Multi-leader, leaderless replication, or even cached systems can’t be linearizable! CAP theorem: When network fault occurs, choose between consistency and availability. e.g. multi-leader replication can work independently (available) when network fails, but aren’t linearizable. - Another tradeoff of linearizability besides fault tolerance is performance. - Causally consistent: as long as system always obeys the right ordering of events - partial ordering: it doesn’t care about concurrent events, just ones with happens-before relation (partial ordering graph are like git version histories with independent branches/ merges). - Implementing casual consistent: - (1) like how we detect concurrent writes on same key, we could generalize version vector to track causal dependency across entire DB. The DB needs to know which data version was already read, so version number from prior operation is passed back on write. DB tracks which data has been read by each transaction, so when transaction commits, it checks if version is up-to-date. Tracking all casual dependencies can get impractical. - (2) Use logical clock, a sequence number assigned for each operation. It’s compact and provides total order. Only works for single-leader. - (3) Lamport timestamp: simple method to generate sequences consistent with causality. The timestamp is a unique pair (node ID, counter). Provides total ordering since if counter is different, we impose that the higher node ID happens before. Every node & client keeps track of max counter it’ve seen so far, and include it in every request. If a node receives a request with max > it’s counter, it increases it’s counter to that max. Cons: order can only be determined after the fact, after you compare against all node counters. In the moment of request, it doesn’t know if another request happened concurrently, and whether to accept/reject.

Consensus

The abstraction you need to make data fault-tolerant & consistent across multiple nodes.

To solve atomic commit for distributed transaction (prevent partial failure), 2PC (see Misc) is common but not very good. 2PC gives safety but often criticized for killing performance and operational problems.

Heterogenous distributed transaction (transaction spans across different vendors) are even more challenging, ex. keeping db and a message broker in sync. If one fails, abort all and safely retry without risking sending it twice to a system. This is possible only if all system has same atomic commit protocol: (1) XA transactions - standard for 2PC across heterogenous tech. Not a protocol but a C library to interface with coordinator. There are limitations like the single point of failure of the coordinator. There’re an alternative though (later)

A consensus must satisfy: Uniform agreement (same decision for all), Integrity (only vote once), validity (vote is registered), termination (decision is made even when some nodes fail - a liveness property. 2PC doesn’t satisfy this)

Total Order Broadcast protocol: implemented by zookeeper/etcd for broadcasting consensus. Each node broadcasts order logs it received and replicate the operations. It guarantees messages are sent reliably in fixed order, but doesn’t guarantee when (network/eventual-consistency). But you can build linearizable storage on top of it - append a distributed log to tentatively claim the username, wait for messages to be delivered back to you, if you get back what you wrote its successful but if it’s from another user you abort. Linearizable compare-and-set, total order broadcast, consensus, are all the same problem

Best known consensus alg: VSR, Paxos, Raft, Zab. Most of them decides on a sequence of values, instead of deciding on 1 value which takes longer time. Total-order-broadcast performs multiple round of consensus, but it only works if there’s a leader, and leader selection is still a consensus problem in itself.. so?

Choosing a leader: It’s possible to make a weaker guarantee by enforcing a unique leader for each ‘epochs’. On election, a new monotonic inc epoch number is assigned. After voting a leader in the quorum, there’s a 2nd round to vote on their proposals - If there’s a conflict between 2 leaders, the one with higher epoch # wins.

This guarantee comes at cost of performance for the syncing process

Membership & coordination services like Zookeeper/etcd are ‘distributed kv stores’. Zookeeper stores in-memory small data that is fault tolerant across db nodes. It provides (1) atomic & linearizable distributed locks (2) monotonically increasing fencing token (3) detect failure if node fails by periodic heartbeats (4) subscribe to value (ie. membership) changes

Part IV: derived data in heterogenous system

No one size fits all solution. App is inevitably going to be heterogenous with different datastores, indexes, caches, analytic systems, etc.

3 types of system: (1) Service / online systems: accepts request, performance measured by response time (2) Batch processing / offline systems: background job consumes data, performance measured by throughput - time to crunch input of certain size (3) Stream processing / near real-time: Between online and offline, it consumes data like batch, but do it as events comes up.

2 types of data systems, determined not by the tools but how you use it: (1) Systems of record: normalized source of truth (2) Derived data system: transformed data. Can be recreated from source if lost. Redundant but provides different pov w better read performance.

Batch processing

Unix tools: are fast and powerful tool for data analyses, ie. awk/sed/grep/sort/uniq/xarg. A program’s output can be ‘piped’ to another’s input, so the program doesn’t need to care about the context (loose coupling / inversion of control). But you need a common interface like file/channel. It is immutable and can buffer to a disk. Limitation: you can’t pipe to a network connection. Just for single machine

Map reduce: kinda like Unix tools but distributed. Requires Job to get their input and output from HDFS, and to have no side-effects. A job breaks input file into records, map to k-v pairs, sort by key (maps a key to a reducer, sorted first per partition then merged by reducer), reducer iterate over sorted pair and combine adjacent keys with same values (shuffle), reducer can generate any # of output records. Workflow is a chain of MR jobs. Specify directory to R/W files, and the ‘workflow scheduler’ handles dependencies between MR jobs. MR handles all network communications, so don’t need to worry about node crashes / retries, it does it transparently.

Higher programming models like Pig/Hive creates abstraction on top of MR.

When ‘joining’ in batch, we try to resolve all occurrences of the association at once to save throughput. The computation should ideally be local (i.e. by copying via ETL prior), otherwise a call to a remote db will introduce nondeterminism. Example processing patterns to ‘bring related data to one place’:

Reduce-side joins (sort-merge joins) using multiple sets of mappers and one reducer. Mappers go through the referenced and referencing table separately and we sort by FK. When we reduce, we merge the 2 sources on the FK.

GROUP BY (group by key and aggregate): set mappers to group by the key. Ex use case: sessionization to bring together user session from multiple servers.

Hot keys can cause skew in amount of data going to each reducer. Strategy: sampling job to determine if keys are hot and distribute the work over several reducers.

Map-side joins: faster than reduce-side join if you can make assumption of the input data. In distributed filesystem, knowing the layout of dataset (size, sorting, partitioning) is important for optimizing join strategies. E.g. Broadcast hash join - without a reducer, each mapper reads entirety of the small input. Even better if inputs is partitioned the same way (ie. already grouped from the output of another MR job), then hash-join can load only the necessary data for that partition (aka. partition hash join or bucketed map join).

Uses of batch: OLAP output reports for BI (ie. metric over time, ranking, breakdown into subcategories). In contrast, a batch process don’t output reports, but outputs a data structure. Ex. build indexes for search engine or full-text search, build ML classifier/recommendation systems which outputs the results to DB, offline processing on graph db.

Writing to DB in a batch job could kill throughput, overwhelm the db, cause side-effects if the job need to restart. Solution: write output as immutable file, then bulk load it to a read-only db.

HDFS uses shared-nothing approach, just computers connected by datacenter network. A central server called ‘NameNode’ keeps track of which file block are in which machine. Blocks are replicated for fail tolerance.

Like data lake, HDFS lets you can quickly dump any raw data to it. It’ll then be processed further by MR for ETL into a DB where they’re carefully modelled, interpreted by the consumer (schema-on-read) using any processing models that aren’t just limited by SQL.

Materialization: intermediate data written to HDFS temporarily for a 2nd job to consume. So MR only start when preceding job fully completes, unlike unix pipes which are lazy.

Other dataflow engines: (ie. Spark, Flink) handles entire workflow as 1 job, rather than independent subjobs. Can pipe operators in more flexible ways, it is generalization of MR and is usually faster. Does Lazy loading for most operation except sorting which must temporarily hold entire state. Recompute from available data for fault tolerance, instead of materializing to tolerate faults - Spark uses RDD and Flink checkpoints operator state. But if it’s expensive to recompute, than materializing maybe cheaper, but otherwise materializing adds overhead.

Stream Processing

A lot of data is unbounded and arrives over time. Stream processing is like running batch process continuously, since dealing with those require batch processor to divide data into windows of fixed duration. Inputs are timestamped events encoded in a file. Published once and subscribed by many just like batch. Related events are grouped as topic/stream.

Alternatively, You could use a DB to store incoming events and let subscribers periodically poll, but the overhead becomes large and it’s better for consumer to be notified. You could directly message consumer from producer without an intermediary: Ex. UDP multicast is used in finance where latency is important, brokerless pub/sub like ZeroMQ, UDP is used by StatsD to collect approx metrics, HTTP/RPC is used in webhooks. In contrast you could rely on Message brokers: runs a server with producers and consumers connected to it. It helps to tolerate unreliable clients with data held by in-mem or on disk. Typically unbounded queueing or expects ‘acks’ from the client before it removes the message or redeliver.

Message systems can take different approaches to publish/subscribe model:

- What happens on consumer lag? system could drop messages, buffer, write overflows to disk, or apply backpressure like blocking producer from sending more (unix pipes/TCP).

- Are messages lost if node crash? durability vs throughput/latency.

- Which consumers do you deliver the messages to? ie. load balancing distribute processing by delivering each message to 1 consumer vs fan-out where each message is delivered to all consumers independently. This matters if you care about Message ordering: if the messages are causally dependent and you want to make sure all the messages in the queue is always performed in order, each consumer must listen to 1 queue, instead of loadbalancing a queue across the consumers.

- Log based message brokers vs AMQP based message queues

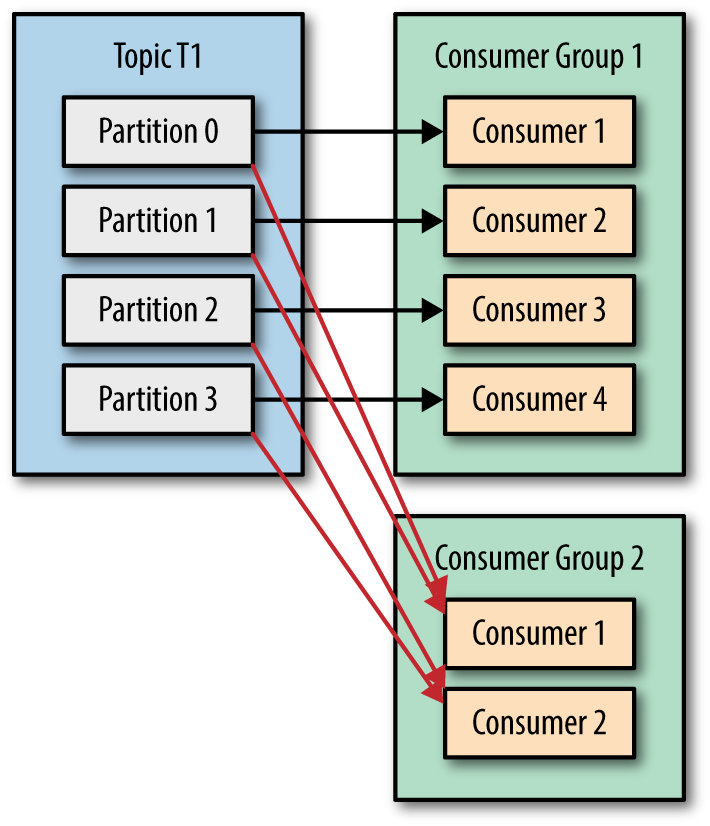

Unlike batch, consuming events can be destructive as it could cause data to be deleted from broker. The idea behind log-based message brokers is to combine durable DB with the low-latency notification. Producers append to log and consumers read from the log sequentially. tail -f watched a file for data appended, and notify the consumers if they’re waiting at the end. Additionally, partition the log for high throughput. A topic can be defined as group of partitions carrying same type of messages. Since partition is append-only, messages within it are totally ordered, whereas there’s no ordering guarantee across partitions.

Consumer groups: with log-based approach, fan-out is trivial since consumer can read them independently without data being deleted. To load-balance across groups, broker assign partitions to nodes in consumer group. Downsides: in a consumer group, # nodes is at most # of partitions. Long-running processes can block the rest of messages in the partition. Thus if messages are long-running, want to load-balance, and message ordering is not important, use traditional AMQP style broker instead of log-based (not persisted FIFO).

Consumer offsets: There’s incrementing sequence # assigned to each message called ‘offsets’. All messages with offset < consumer’s current offset, has been read. Broker don’t need acknowledgements; only periodically recording the consumer offsets. If consumer node fails, another node in the consumer group takes over at last recorded offset. You can always replay old messages by copying the consumer and set it to yesterday’s offset. This makes it like batch, where transformations are repeatable.

Ring buffer: Logs are segmented with old ones deleted/archived, but is pretty large since buffer is on disk. Monitor consumer lag to raise alert before slow consumer starts missing messges.

Streaming for derived data systems

Replication log is itself a stream of db write events, from leader to followers.

Using streaming to keep systems in sync: When updated in DB, data must be updated in the cache, search indexes, data warehouse, etc. (1) Use batch process like ETL to load new data to warehouse, re-index. Can be slow. (2) Use dual writes. Atomic commit with 2PC is expensive. (3) CDC: expose replication logs as an API for other systems to consume, rather than an internal detail in DB. Implementing: Using DB triggers can be fragile with large performance overhead. Parsing the replication log is more robust. ie. Kafka connect offer many CDC connectors.

Building new derived data system: CDC logs will be truncated after some time, but if you need a full copy of the db… (1) Record snapshots (2) Log compaction: mark a thombstone on duplicate keys for log compaction so space isn’t proportional to write history. Every CDC change updates previous values of the same key. When you need a full copy of db, you could start from offset 0 of the log-compacted topic. This is supported by Kafka.

CDC is beginning to be first-class interface. RethinkDB, Firebase, CouchDB allows you to subscribe changes, so external data system can derive from this log.

Event Sourcing: is a pattern similar to CDC, but events are created at app logic and reflects events rather than low-level state changes. Deriving state needs the whole history / snapshot, since compaction isn’t possible. Commands are synchronous requests, while events are immutable facts when the commands are validated and accepted. You could split events in 2 - a tentative reservation, and a confirmation/rejection event.

Mutable state and immutable events are 2 sides of the same coin. State is integration of events over time. Immutable events recovers easily and captures more information than just latest state.

The write-optimized event log could derive different read-optimized views, such that debates around normalization/denormalization become irrelevant as long as you keep data consistent. However keeping derived system in sync without delay (reading your own writes) pose the same challenges as distributed systems.

Immutability also has limitations: (1) compaction is expensive when there’s high update/delete rate (2) if data need to be deleted (ie. GDPR or accidental leak), you wish to rewrite history, not just append. Deletion is hard, and often more of ‘let’s make it harder to retrieve’

Stream Processing In Practice

Once you have the stream, you can:

- create derived data and keeping it in sync

- push the events to users in the form of push notifications or visualization

- Processing streams! process >=1 input streams to produce >=1 output streams.

🪅 Uses:

Could be used for monitoring/alert purposes like fraud detection systems to check credit card usage patterns, trading systems to check price change and execute trades, manufacturing system to monitor status of machines, etc.

The Complex event processing (CEP) approach is to analyze event streams by finding pattern matches to a query. When match found, processing engine emit a ‘complex event’. Reverse the role of data & queries in normal db: query being long-term instead of transient.

Search on streams: like CEP but perform searches within individual events. I.e. full-text queries, media monitoring services subscribe to feeds and search for mentions of topics, get notified when new real estate matching their search criteria appears on the market. Percolator feature of ES is an option to implement this. It can be slow to run every document against every query. An optimization is to index the queries as well as the documents to narrow down the set of queries to match.

Stream analytics: less about finding events, but toward aggregations/metrics over large events. I.e. rate, rolling average, detect trends over windows. Use probabiilstic algorithms like bloom filters, hyperLogLog, percentile estimation to approximate results.

Materialized views: Generalizing derived states. Need beginning of time events.

🪅 Implementations:

Stream operator/job is similar to unix process, map reduce jobs, and dataflow engines. The only difference is stream never ends - so sort-merge joins can’t be used, and has its own strategies of fault-tolerance since you can’t restart from beginning.

3 types of stream joins:

- Stream-stream (window) joins: the processor maintain state for the streams, and emit events after the join time window. E.g. to calculate Ad click-through rate, you could store ‘visit’ and ‘click’ events indexed by session ID. Then, emit clicked event if there are both events and not clicked event when there’s a visit event but it expires without seeing a matching click event. The click may be delayed, out of order, or never come.

- Stream-table (stream enrichment) joins: For each event, the processor remotely query DB, or if it’s small, load a DB copy to be queried locally (like map-side join). That DB needs to be updated via CDC, so processor will have 2 inputs: table changelog stream + the input stream. I.e. joining user profile with a stream of user activities.

- Table-table joins (materialized view maintenance): the output represents a join between 2 tables, aggregated in some way, but maintained as a continuous stream. E.g. to keep twitter’s timeline cache you join ‘tweets’ and ‘follows’ table to distribute the tweets to the every follower (output is a follower with aggregation of tweets).

🪅 Challenges:

Slowly changing dimension (SCD) problem: the timing of the join matters to determine order. Solution: append a unique version identifier. But this prevents log compaction since that’ll remove the versions.

Fault tolerance: in batch it’s easy to restart due to immutable input and the output is only written once everything completes. Can’t do this in streams because processing never ends. Solutions:

- Microbatching & checkpointing: break stream into batches (in spark-streaming), or generate rolling checkpoints of state to recover when operator crashes (in Flink). But you can’t discard output once it leaves the processor, so restarting causes side-effects.

- Atomic commit: output and side-effect takes effect iff successful, used in more restricted non-heterogenous envs like Google Cloud Dataflow, Kafka.

- Idempotence: operations you can perform many times, like setting a key or storing metadata so you don’t perform the update again.

Time window challenges: many processing frameworks use system clock instead of event time to determine window for simplicity, but breaks down if there’s processing lag, along with mis-ordering of messages. Leads to bad data (like unintended spikes when processor comes back up from failure). But if event time was used, (1) the source device’s local clock can’t be trusted. An approach is to approximate the offset as (server received time - device send time) (2) Processor won’t know if there’re more events to come to include in the window. Staggler events could come delayed if it’s buffered elsewhere like an offline mobile app or network delay. You could either drop them since it’s a small % and alert if too much is dropped, or publish a correction.

Evaluating stream processing

Distributed transactions (2pc) vs derived data (sync vs async): Both provides ordering and atomic guarantees, but transactions provides stronger linearizability guarantees since it’s sync. Async log is more robust/loosely-coupled than distributed transactions.

Deriving data helps evolve apps: You can restructure dataset for new requirements (schema migrations). Allow you to maintain old/new schema side-by-side and maintain different views of your app. Gradual migration is easily reversible at every stage.

2 philosophies: UNIX/hadoop provides ‘simple’ low level wrapper around hardware, SQL provides ‘simple’ high-level abstractions that hides all complexities. Unbundling databases: Derived data systems works like indexes of a huge DB running various software, machines, and teams. You could see 2 ways different tools integrate: (1) Federated DB / unifying reads provide unified query interface to a variety of systems. (2) Unbundled DB / unifying writes sync writes across diff systems.

DB events aren’t just async jobs: You could treat DB events as messages that actors/app subscribes and responds to, but that won’t work if order and fault-tolerance matters.

Treating read as events: read events could also be stored or streamed through a processor. Allows you to do stream joins on the DB, track causal deps (analyze user behavior) but incurs extra I/O and storage. This idea opens up possibility of query/joining multiple partitions of data (ie. apache storm distributed rpc feature).

Subscribe vs Querying argument:

- Stream processor vs REST in microservices: Streaming is fault tolerant and performant. You could subscribe to events and store the most recent to db locally (stream to a cache) so when it’s needed no network call is needed. But it goes in one direction instead of req/res.

- Write path (pre-computation stages for data to flow to derived systems - eager load) and Read path (flow of data when consumers ask for it - lazy load): Derived data is where write path meets read path, and defines tradeoff between write-time work vs read-time work. The role of caches shift the boundary between write/read path, determined depending on the load.

- Idea of stream processing applies to stateful client (websockets/eventsource-api). When user lags behind it could keep up via log brokers. Why not extend the write-path all the way to users? The challenge is supportability in our libraries/protocols/db/frameworks.

Enforcing write constraints

Uniqueness: funnel all through single node, otherwise requires distributed consensus. You could also use stream processor to partition the unique key (each partition is total ordered), join the states, and emitting success/reject. But it’s async.

For write constraints involving multi-partition (ie. payee, payer, request_id), using transactions to couple partitions would kill throughput. Turns out you could equivalently use stream processing to avoid atomic protocol! Distribute the multi-partition write request to multiple streams (need this step for atomic commit to ensure all or neither commits happens) to be processed on each partition independently. On crash, it’ll retry and downstream should dedup.

Dealing with async: Unlike transactions, streams aren’t linearizable. Consistency could mean timeliness (up to date state) or integrity correctness (no permanent corruption). Streaming system keeps integrity with low performance but no guarantee on timeliness. Solutions:

- You can subscribe to the output stream for result.

- Weaker constraints: it’s often acceptable to violate constraint, write optimistically and apologize after. Eg. ask them to rebook/rename/reorder/refund. If the cost of apology < cost of performance/availability.

Part IV: Future of data systems

When zooming out, there’s so much things you do with all the dataflows. (ie. caches, data analysis from warehouse, ML systems, notifications, etc)

Be very clear of input/output of data systems. Funnel all input through 1 system so ordering writes become easy and consistent.

Developments:

- As you scale, order isn’t guaranteed across partitions/systems (ie. microservices deploy states independently). Causal problems often arise in subtle ways (e.g. unfriend event & message send could be causally dependent). Ordered consensus is an open research.

- Batch & stream is beginning to blur - Spark perform stream processing on top of batch engine. Flink performs batch on top of stream engine.

- Lambda architecture: running stream processing for quick latency, then re-running same processing w batch to perform more reliable and exact algorithms.

- Differential dataflow: defining materialized views via complex queries

- Spreadsheets have dataflow capabilities ahead of most languages. Views/aggregations/index of records can recompute automatically. However, we need that to be fault-tolerant, scalable, durable, and evolve with different tech / teams.

End-to-end argument: Data corruption/correctness should be considered holistically. Low-level reliability features aren’t sufficient, and it’s hard to abstract away fault-tolerant mechanisms from the user. Immutability isn’t a cure-all. You need exactly once semantics / idempotent, to make it retry-able. Transaction don’t always ensure idempotence. E.g1. A transaction crashes as soon as it commits, the node retries as a new tcp connection when it comes back. E.g2. client crash after sending post request, they manually retry after seeing the error msg, which makes separate transactions.

Ensuring idempotence require dedup methods that considers end-to-end dataflow. E.g. You could use a unique request_id generated client-side (event log) and the DB transaction is performed with that id as unique column.

Data Ethics

Datasets are about people, treat them with humanity. Ethics is difficult but is too important to ignore.

Discrimination: Predictive analysis is used to determine risk of bad loan, fraud, insurance coverage, hiring trustworthy people, property rental, air travel. Organizations naturally want to be cautious and better off saying no. These affects individuals and systematically exclude people from aspects of society without proof of guilt / chance to appeal (algorithmic prison). Algorithms will learn and amplify systematic biases we input. They extrapolate from the past, and a discriminatory past will be codified. We need humans and moral imagination to model a better evolved future.

Accountability: It’s hard to trace how ML algorithms make decisions. Ie. Going by “How did you, or people like you behave in the past?” implies stereotyping. Statistical data will be wrong on individual cases. (interceptor movie meme)

We need to make algorithms transparant, avoid reinforcing biases, fix mistakes, prevent its use to harm people; e.g. data focused to aid support for those in need instead harming the most vulnerable people.

Feedback loops and echo chamber breeds stereotypes/misinformation/polarization. Involve systems thinking when considering consequences.

Data collection: user is no longer the customer when the service acts on the data with its own interests which may conflict with the user’s. Advertisers are often the actual customers with user engagement being the product. Startups are valued by their surveillance capabilities. Corporates targets marginalized minorities the most. Data analysis can also reveal a lot (ie. smartwatch sensor can work out what you’re typing). Users have little knowledge of the derived data, there is no option/dialog to negotiate how much data they’re willing to provide (terms are set by service not user), there could be costs to people not using a service and the less privileged has less freedom of choice. Surveillance has never been this scalable and automated.

Privacy: the freedom to decide what you want to disclose to whom. These rights are often transferred to the data collector, and companies exercise those rights for them with the goal of maximizing profit. Algorithms are oblivious to personal judgements of what data is undesirable/wrong/inappropriate.

Data as toxic assets: it could land into the wrong hands, ie. data leak, bad management, the political env of tomorrow. Knowledge gives power to scrutinize others while avoiding scrutiny to oneself. Data is the pollution problem of the information age just as industrial age left us with problems that took long to safeguard, regulate, and putting a cost for businesses that benefit the commons. Between the tradeoff of over-regulating risks and preventing breakthrough, companies should self-regulate through a culture shift.

Miscellaneous

Happens-before relationship vs Concurrency: Operation A happens before B if B knows/depends-on/builds-upon A. While 2 operation is concurrent if neither happens before the other (don’t know each other)

Algorithm to capture causal dependencies. Detect Concurrency vs Happens-before:

DB maintain version # for every key, and increments it on every write. Client merges the values it reads, before writing them back (e.g. union, attach tombstone on deletion, RIAK supports CDRT data structure to do auto merge, include conflict resoltuion).

The DB overwrite values with version number <= the request version number (happens-before), and keep higher version number (concurrent) as siblings.

For leaderless and multi-replicas, it’s the same but need version number per each replica & per key. You’d have a version vector: collection of version number from all replica.

A ‘coordinator’ assigns txID unique to the transaction. Phase 1: when ready to commit coordinator send a prepare request to each nodes if they can commit. If response is all yes, it send a Phase 2 commit request, else, abort request to all nodes. By replying ‘yes’ the node promises to commit tx without any error. And when coordinator make the final decision, it logs a commit point to disk in case it fails, and decision must be enforced no matter how many retries.

However, 2PC is vulnerable to coordinator failure when the nodes is left blocked / in doubt from not receiving the 2nd phase’s confirmation (thus 2pc is a blocking atomic commit protocol). This is a problem since locks are often held in transactions and so can’t be released if blocked, making the app unavailable until resolved. The only way is for an admin to manually make the decision.